Format: Hardcover. You can purchase it on Amazon

- Publisher: Petr Prchal

- Publication date: 1989

- Language: English

- Print length: 206 pages

- ISBN-13: 978-0805009606.

The Hungarian edition was published by Typotex Publishing Ltd. in 2015 and can be purchased at Typotex.

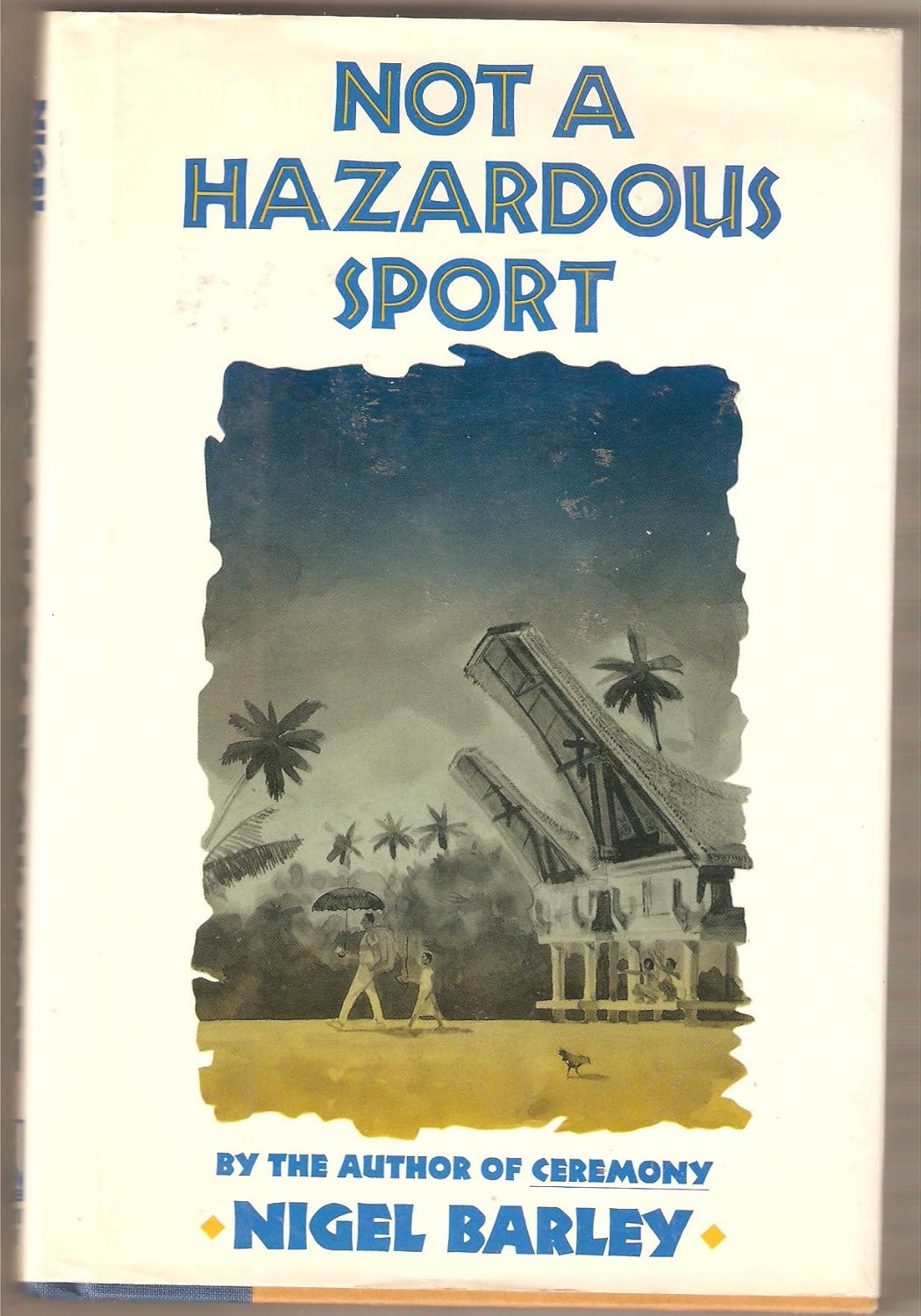

The name of Nigel Barley may be familiar to readers thanks to his unforgettable and humorously written book The Innocent Anthropologist, in which he recounted his time spent among the Dowayo people in Cameroon. The second of his works to be published in Hungarian is the wildly entertaining Not a Hazardous Sport, which was released for this year’s Book Week. The statement that serves as the title of this 1989 travelogue came from a correspondence the author had with his insurance company before embarking on his journey. His written experiences somewhat contradict this assertion, but Barley is hardly a greenhorn traveler. In Africa—where he nearly lost his life—he became well-seasoned enough to navigate a world completely foreign to Europeans. He also possesses the humor and self-irony needed to endure difficult situations.

Now 68 years old, the British anthropologist originally studied modern languages at Cambridge before earning a doctorate in cultural anthropology from Oxford. He later worked in the office of a metal trading company, but found the profit-driven, soulless work unappealing. He then became a curator in the ethnographic department of the British Museum, where he worked for twenty years. In an interview, he once said, “One day they left my office door open, so I escaped.”

Since 2003, he has worked as a freelance writer, traveler, lecturer, consultant, and radio presenter. He has explored many fascinating places around the world and lived in India, Japan, and West Africa. His Indonesian destination was the island of Sulawesi, specifically the land of the Toraja. The Toraja culture is well known for its distinctive architecture, cliffside tombs, and wood carvings. Since the era of Dutch colonization, the region has been a popular tourist destination. Even thirty years ago, the effects of globalization were already noticeable. Traditional Toraja culture was beginning to dilute, and Islamism had started to emerge in the region.

Barley portrays the everyday life of this transforming society with gentle humor and sensitivity, free from any sentimental enthusiasm for ancient customs. He paints a peaceful picture; the religious and ethnic tensions that would later escalate in the region are not yet apparent in the book. At that time, the world wasn’t paying much attention to Southeast Asia, and we still know little about the social transformations that occurred there—changes which may be echoed in our own societies in the future.

As a special treat at the end of the book, Barley presents the oddities of cultural encounter from a reversed perspective. He invited a few Toraja woodcarvers to London to build a replica of a rice barn. Here, it was the Toraja who became the anthropologists, interpreting the everyday habits of Western culture just as researchers typically interpret those of “natives.” A thought-provoking and timely read.