Architects have been fascinated by moving buildings since the late 19th century. In nature, most things move in some way, whereas traditional architecture creates rigid, static structures made of stone, wood, and more recently, steel and glass. Various experiments have been made to somehow bring buildings to life, and one such approach is the concept of rotating houses.

The pioneers of breaking away from rigid, geometric forms were the proponents of organic architecture—Antoni Gaudí, Rudolf Steiner, Friedensreich Hundertwasser, and others. They cannot all be grouped under one umbrella, but the use of curved, flowing forms characterizes the movement as a whole. They sought to use nature as a model for their buildings, yet their structures remained static, like rock formations. The path to truly dynamic, moving buildings began with Tommaso Francini’s invention: the revolving stage. This rudimentary device for rotating stage scenery was first presented at the Louvre in 1617. The first real, heavy-duty revolving stage, with a diameter of 15 meters, was built by Karl Lautenschläger in 1896 in Munich’s Residenztheater[i]. Lautenschläger’s structure operated on the same principle as another significant invention of the Industrial Revolution: the railway turntable. The turntable consists of a steel bridge-like structure recessed into a circular pit, which rotates around a central pivot called the kingpin. The bridge rests on a circular rail at the edge of the pit and moves on wheels along it. A locomotive or other railway vehicle rolled onto the bridge can be rotated 180° or directed onto any of several connecting tracks. Lautenschläger’s stage worked in the same way, except instead of a railway bridge, it had a platform that completely covered the pit, allowing stage sets to be built on it and rotated as needed.

A House on a Turntable

I don’t know about you, but waking up to the light of the rising sun and sipping coffee in the soft morning glow is wonderful. That’s why a bedroom facing east is great. At bedtime, though, it’s nice to drift off in the last crimson rays of the sunset, which makes a west-facing room the ideal choice. Of course, you could have windows facing both east and west, but then the room feels like a hallway, lacking that cozy “nest” feeling. It’s like living in an aquarium—and it can get drafty too. If you want your room to always face wherever feels most pleasant, the solution is a rotating house!

In the 1930s, in Marcellise near Verona, Italian engineer Angelo Invernizzi designed and built the Villa Girasole—the Sunflower Villa—for himself. Invernizzi worked for the navy and was perhaps inspired by the massive rotating gun turrets of dreadnought battleships. At first glance, the house appears to be a more or less conventional L-shaped building with a central tower. In reality, the tower is much taller than it looks—42 meters, half of which is below ground. This is the structure’s rotational axis.

The house sits on a 44-meter-diameter circular base that rolls on 15 pairs of wheels along a rail, similar to revolving stages and railway turntables. Its maximum peripheral speed is 4 mm per second, and it takes 9 hours and 20 minutes to complete a full rotation. Two diesel engines provide the power for rotation.[ii]

Invernizzi and his design team experimented with various materials, from concrete to fiber cement. Concrete has very low tensile strength and kept cracking, so in the end, the frame was clad in aluminum sheets. Here’s a drone video of this unusual, though not particularly aesthetic, structure:

The attached photo clearly shows one of the structure’s drawbacks: it must be rotated even when the occupants don’t need or want it, otherwise the grass beneath it will die. Recently, a proposal was made to power the rotation with electric motors and solar panels, as the building’s ability to rotate offers an excellent opportunity for optimal solar panel placement.[iii] The villa remained in the possession of Invernizzi’s descendants until 2002; today, it is maintained by a foundation.

Invernizzi’s turntable-based solution inspired several followers. One example is the “UFO of Martigny” in northern France, which now operates as an accommodation:

In Belgium stands François Massau’s rotating house, La Maison Tournante (Wavre, 1958). Norwegian builder Jarle Hegerland, on the other hand, did not abandon the traditional house concept—he simply placed his home on a rotating platform. He and his family wanted to enjoy both sunrises and sunsets as well [iv]:

A couple from San Diego, Al and Janet Johnstone, also envisioned a rotating home for themselves. Completed in 2004, the house even has its own website (rotatinghome.com), and several films have been made about it:

This house rotates relatively quickly, completing a full turn in just 33 minutes. The Australians didn’t want to miss out on the fun either—in fact, they immediately turned it into a business venture. The prototype of the Everingham Rotating House was built in 2006. Its owner and designer, sound engineer Luke Everingham, aimed primarily for ecological construction, tracking the sun’s movement, and playing with light and shadow. The project’s website even offered these houses for sale in versions capable of rotating 180 or 360 degrees, but it seems the venture was not successful, as the site is no longer accessible at the time of writing.[v]

Chicken Legs and Other Delicacies

Although the general public hardly noticed, the design and construction of steel structures have advanced significantly in recent decades. Just take a look at the Elizabeth Bridge! It’s worth noting that the pylons of this modern cable-stayed bridge, designed by Pál Sávoly, are riveted! At the time of its construction (1964), experiments with welded structures were already underway, but neither the materials nor the technology was adequate yet. The Kossuth Bridge (1946), which connected Kossuth Square and Batthyány Square, was intended for a lifespan of just ten years and built from wartime scrap metal—yet problems with cracked welds appeared almost immediately after it opened. Welding technology only reached the point in the mid-1970s where reliable, heavy-duty structures could be made with on-site welding. The results can be seen, for example, in the Lágymányosi Bridge.

This progress also impacted the builders of rotating houses: they were finally able to abandon the cumbersome turntable and imagine new geometries.

Near the city of Rimini, the Casa Ruotante was built based on designs by architect Roberto Rossi. Standing on a slender column, it truly looks like the kind of rotating house one imagines when hearing the phrase “a house on chicken legs.” The 150 m² structure can rotate 360 degrees in either direction and was constructed by the Italian construction company ProTek:

A major challenge was ensuring that the structure could withstand the stresses caused by rotation, which is why it was built with a steel frame, while its walls are made of wood with hemp and wood fiber insulation. The goal of the rotation was not only to provide a variety of views but also to position the solar panels for maximum efficiency at all times. The house is fully passive and capable of generating all the energy it needs for operation. In addition to solar panels, it is equipped with solar thermal collectors and a heat pump heating system.[vi] Thanks to its construction technology, it can be easily dismantled and relocated.[vii]

Thirty years ago, in his hometown of Freiburg, Germany, Rolf Disch (www.rolfdisch.de) faced a major debate: the city was considering building a nuclear power plant. Many citizens fought hard against the plant, including architect Disch, who responded with a revolutionary concept—a house capable of fully supplying its own energy needs.

This was the Heliotrope, a milestone in architecture: the first PlusEnergy house in the world—an active house that harnesses geothermal and solar energy and produces more energy than it consumes. The cylindrical building has an open, glass façade on one side and an insulated wall on the other. The entire structure rotates on a massive ring gear. In winter, the glass façade faces the sun, while in the hot summer months, the insulated side turns outward.

Despite its innovative concept, the building’s curved interior spaces failed to achieve broad popular appeal, and only three were ever built (Breisgau, 1994; Offenburg, 1994; Hilpolstein, 1995).[viii]

The Portuguese company Casas em Movimento designs solar-powered homes using unique technological solutions. They have already produced several prototypes. Like others, they take advantage of the “sunflower effect,” but their building volumes are significantly more conventional than the Heliotrope. In their designs, either the external frame carrying the solar panels moves, or the entire block-like structure rotates:

How livable such a house really is can be hard to judge without firsthand experience, and there may also be issues with land use—what happens if Dad leaves the car in the rotation zone? For dynamic houses, the risk of the building hitting something is a very real concern. With the Dynamic D*Haus concept designed by Daniel Woolfson and Ben Grunberg (thedhaus.com/portfolio/the-dynamic-dhaus/), this is especially true—but there’s also the question of whether you can even find the bedroom at night!

The structure is based on a fundamentally simple, cube-like form, but thanks to its hinges and curved tracks, it can fold itself into a completely different shape. Definitely worth watching on video:

Of course, not everyone sticks to single-family home dimensions. Bruno de Franco has designed a tower about 50 meters tall, with 11 rotating floors:

The Suite Vollard was completed in 2001, with apartments selling for $400,000 each. The British firm Studio RHE is planning a hotel on the island of Šolta (Croatia), which will become Europe’s first rotating hotel. In Antalya, a popular resort city in the Asian part of Turkey, there is already something similar—although not the entire 214-room Hotel Marmara Antalya rotates, only an additional rotating block with 24 rooms. Architecturally, the hotel is rather unremarkable, but its stunning seaside location and the rotating wing attract plenty of tourists (www.themarmarahotels.com).

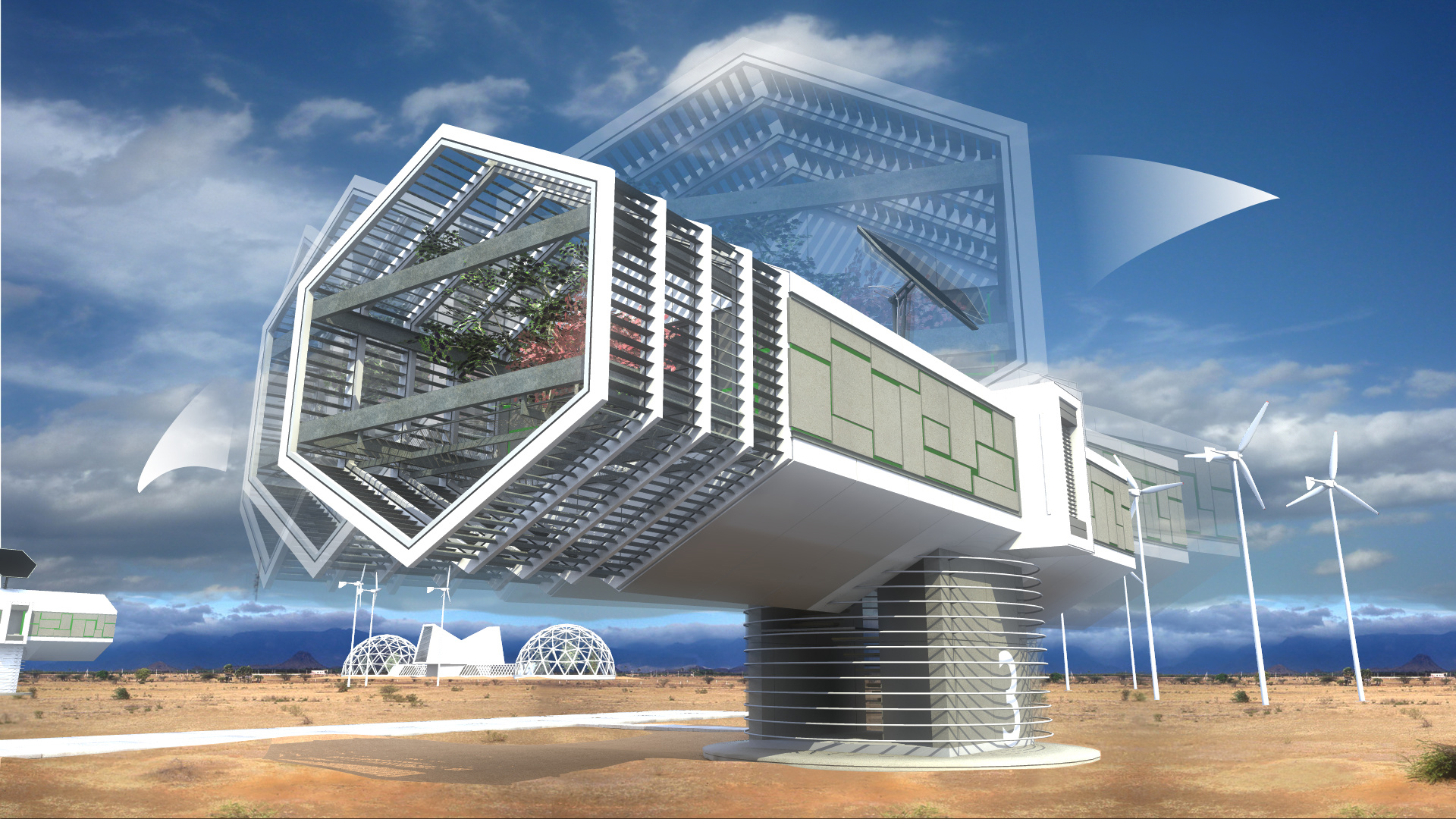

And of course, when it comes to large and unusual buildings, we have to mention Dubai! The concept envisioned by Italian architect David Fischer is a true shape-shifter: it will continuously change its form throughout the day, taking on a different appearance at every moment:

Apparently, this dynamically moving skyscraper was planned to be completed in the Emirates by 2020, but so far, nothing has come of it. The idea isn’t new—Fischer had previously envisioned similar projects for Paris, London, New York, and Moscow. Back then, the construction cost was estimated at $330 million.

The 420-meter-tall, 80-story tower would not only have been the first in the world to change shape continuously, but also the first prefabricated skyscraper. According to Fischer, 90% of the tower could be manufactured in a factory and transported to the construction site. Prefabricated elements would reduce project costs, the number of workers required, and construction time.

Of course, the skyscraper was also marketed as “green”: the entire tower would have been powered by wind turbines and solar panels. In fact, Fischer claimed it would “be able to produce 1.2 million kWh of energy.” To add my two cents, this statement makes little sense, as Fischer never specified over what time period this amount would be generated. For context, the Paks Nuclear Power Plant produces that in just over half an hour, while a bicycle dynamo could also produce it—if you pedaled for 45,000 years.

Anyway, the point is that Fischer claimed there would be such an abundance of green energy that they could even power five additional towers like this one. In 2008, Fischer said he expected the skyscraper to be completed in 2010; then, in 2009, he said construction would finish by the end of 2011. Incidentally, Fischer admitted he had never built a skyscraper before and hadn’t practiced architecture for decades—but, in his words, that wouldn’t be a problem.

For now, construction hasn’t started, and no official announcements have been made from the proposed site.

Chicken Legs in Hungary?

If anyone in Hungary feels inspired to build a real house on chicken legs, I have good news—and bad news. The good news: since January 1, 2017, no building permit is required for residential buildings with a usable floor area of less than 300 m²—only a simple notification is needed. This was a bureaucracy-reducing measure.

The bad news: under a government decree, municipalities were required to prepare a Local Architectural Identity Manual[ix], which dictates building heights, roof shapes and slopes, placement on the plot, colors—even the height and transparency of fences. While no permit is required, compliance with these rules is “voluntarily mandatory.” If your building does not fit the prescribed visual character, the designer and the builder can be fined, and the construction can be halted by the building authority or the local municipality.

A pseudo-Baroque farmhouse with an attic conversion and a swimming pool might pass muster, but a “rotating thing” would probably stick in the throat of the local bureaucrat. As Témüller sings in The Attic musical: “Uniform houses and flat rooftops / We won’t tolerate those oddball types.”

I can’t help but wonder—would such a Témüller have a stroke if the house that was a quaint white farmhouse with a red gable roof and a porch in the evening transformed itself overnight into a futuristic, black-metal, Cubist wonder?

Sources

[i] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Revolving_stage

[ii] http://architectuul.com/architecture/villa-girasole

[iii] https://www.archinform.net/projekte/4123.htm

[iv] http://bobedre.dk/indretning/inspiration/roterende-hus-muliggoer-sol-hele-dagen

[v] http://www.mgsarchitecture.in/projects/446-everingham-rotating-house-australia.html

[vi] https://www.dezeen.com/2018/03/30/rotating-house-italy-roberto-rossi-moving-building/

[vii] https://worldarchitecture.org/articles-links/ehcvm/roberto_rossi_completes_a_fully_rotating_house_in_italian_countryside.html

[viii] https://inhabitat.com/heliotrope-the-worlds-first-energy-positive-solar-home/

[ix] https://epitesijog.hu/2009-utmutato-telepleskepi-arculati-keziknyvek-keszitesehez