“Words can act like tiny doses of arsenic: they are swallowed unnoticed, they seem to have no effect, and then after a little time the toxic reaction sets in.” — Victor Klemperer

You can download it free from Internet Archive, or purchase it on Amazon.com.

- Publisher: Continuum

- Publication date: 2006

- Language: English

- Print length: 288 pages

- ISBN: 978-0826491305

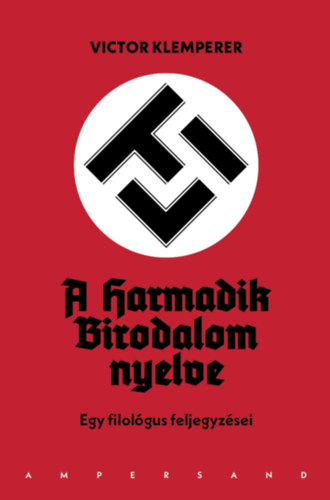

The Hungarian edition was published by Gabo Publishing in 2015 and can be purchased at & kiadó, 2022.

Victor Klemperer’s book Lingua Tertii Imperii was first—and until now last—published in Hungarian in 1984, in the Membrán Books series of the Institute for Communication Research. The author, cousin of conductor Otto Klemperer, was professor of linguistics at the Dresden University of Technology from 1920. Although he had converted to Protestantism twenty years earlier, after the Nazi takeover he was stripped of his academic chair because of his Jewish origins. Working as a manual laborer, he could closely observe how the Nazi regime brainwashed ordinary people. His wife, Eva, was of “Aryan” descent, and thanks to her he escaped deportation. During the bombing of Dresden, exploiting the chaos, he fled to an area under American control, thus surviving both the end of the war and Auschwitz.

He followed changes in language use from 1933 onward, recording even the tiniest details of everyday life in his diary, as well as documenting political and social events, the rise and deepening of terror. His notes, originally written in Latin and German, were first published in German in 1947, and later appeared in English in three volumes. The first two—I Shall Bear Witness (1933–1941) and To the Bitter End (1942–1945)—depict the period of Nazi terror. Although the “language of the Third Reich” originated within the narrow elite of the Nazi Party and was shaped primarily by Joseph Goebbels, Minister of Propaganda, it quickly spread to wide audiences, entering the legal system, the economy, the arts, science, and even sports. Hitler’s success was greatly aided by this new style of communication, for power can be expressed not only through physical violence, but through language as well. By distorting the meaning of words and inventing new ones, the regime created a surreal world detached from reality, in which duped little people staggered about as fanatical believers.

After the war, Klemperer became a significant cultural figure in the GDR and a delegate to its parliament. Yet in his third diary volume, The Lesser Evil (1945–1959), he repeatedly hinted at his growing disillusionment with the new socialist state. He died in Dresden in 1960, at the age of 78.

LTI was republished in reunified Germany in 1995, achieving great success. Prestigious journals presented Klemperer’s life in detail, and documentaries were made from his notes. His remarkable insight, intelligence, clarity, and biting humor won the hearts of many. In Mein Kampf, Hitler contemptuously speaks of the “Objektivitätsfanatiker” (fanatics of objectivity), declaring that instead of complex facts, primitive slogans must be hammered into people’s heads—and he does not even hide how stupid he considers his own people, whom he thus found easy to train. Klemperer defies such expectations, and in fact takes a certain grim amusement in it. This book, laced with gallows humor, is his revenge. We read it with a shiver and an uncanny sense of déjà vu.

Lingua Hungaricae Imperii? Language, like a mirror, shows us not only what we are but also what others would like us to be. In Hungary, as elsewhere, political power reshapes the meaning of words until they no longer describe reality but create a new one. Just as in the Third Reich, everyday expressions are pulled from their neutral contexts and charged with ideological current.

Take nemzeti. Once the word of poets and historians, it meant the whole people, our common heritage. Today it serves as a government trademark: Nemzeti Dohánybolt, Nemzeti Konzultáció, Nemzeti Közművek. What is “national” now? Simply: “ours, the state’s.”

So too with konzultáció. Consultation, in a healthy language, is dialogue. In practice it has become a monologue printed on millions of forms: “Do you support Hungary’s right to defend itself against illegal migration?” The answer is built in. The word that promised reciprocity now enforces obedience.

Even rezsi, once the dull total of gas and electricity bills, has been exalted. With rezsicsökkentés, it is no longer a burden but a symbol of the government’s fatherly care. To say “rezsi” is to give thanks, not to complain.

Other words are twisted into weapons. Migráns was once a statistical term. Today it is a curse, conjuring nameless hordes, criminals, terrorists. Its sympathetic twin, menekült (refugee), has been banished from the stage, for it might arouse compassion. Civil once meant “citizen organizing freely.” Now it suggests “foreign agent,” “paid outsider.” Even ellenzék, the legitimate opposition of parliament, is stripped of dignity, painted instead as “dollárbaloldal,” as traitors in the pay of strangers.

Geography itself is not spared. Brüsszel is no longer a city but a phantom enemy, blamed for diktats and conspiracies. The syllables carry not a place but a threat.

The rhetoric of protection completes the picture. Béke—peace—has been nailed to billboards. Not to describe foreign relations, but to declare: only we guard you from war. Megvédjük—“we will protect”—is repeated like a church litany: we protect families, pensions, utilities. By repetition, it creates a constant atmosphere of siege. Citizens are taught to see themselves as surrounded, yet forever saved at the last minute.

And then szuverenitás. Once the proud independence of 1848, now brandished to resist Brussels, NGOs, journalists. The word has been narrowed until it no longer means freedom of the people, but freedom of the government from scrutiny. A special office, the Szuverenitásvédelmi Hivatal, promises to “defend” sovereignty, though in practice it means defending power against criticism.

The moral vocabulary, too, is enlisted. Gyermekvédelem—child protection—should mean safeguarding against poverty, hunger, violence. Today it is reduced to censorship, to the exclusion of LGBTQ+ themes. Children are not shielded from abuse, but from information. Keresztény—Christian—no longer designates the disciple of Christ. It is a badge of loyalty to the government’s world-view, a cultural marker without need for faith or prayer.

Even the word közmédia is corrupted. It once meant media of all for all. Today “public” means state, and “balanced” means uniform.

These examples show how power still corrupts meaning. Just as the Nazis elevated the banal into the sacred and the brutal into the natural, today’s Hungarian politics inflates neutral words into slogans, deflates noble ones into accusations, and thereby creates a linguistic fog. Through this fog, citizens stumble—half-believing, half-mocking, but always surrounded by the dull hum of words that no longer say what they mean.

Thus a whole vocabulary shifts. Dialogue without dialogue (konzultáció), consultation without society (társadalmi egyeztetés), media without plurality (közmédia). Neutral terms are armed, noble terms are emptied, and all words march in step to the rhythm of power. And here lies the danger. When words lose their older meanings, citizens lose the ability to name reality. They can only repeat the slogans, or else fall silent.

Klemperer once wrote that words act like tiny doses of arsenic: swallowed unnoticed, harmless at first, and only later the poison works. In Hungary today, too, the vocabulary of politics sweetens itself with “protection,” “peace,” “national.” But the aftertaste is bitter.